Introduction

Archibald Campbell Carlyle (1831–1897), First Assistant of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), was a pioneering British archaeologist whose life was devoted to discovering, preserving, and restoring India’s ancient heritage. He is particularly renowned for his meticulous work at Kusinagar, the site where the Buddha attained Parinibbāna, and for his tireless search for other historically significant Buddhist cities, including Pāvā. Carlyle’s dedication was not motivated by fame or wealth but by a profound respect for history and the teachings of the Buddha.

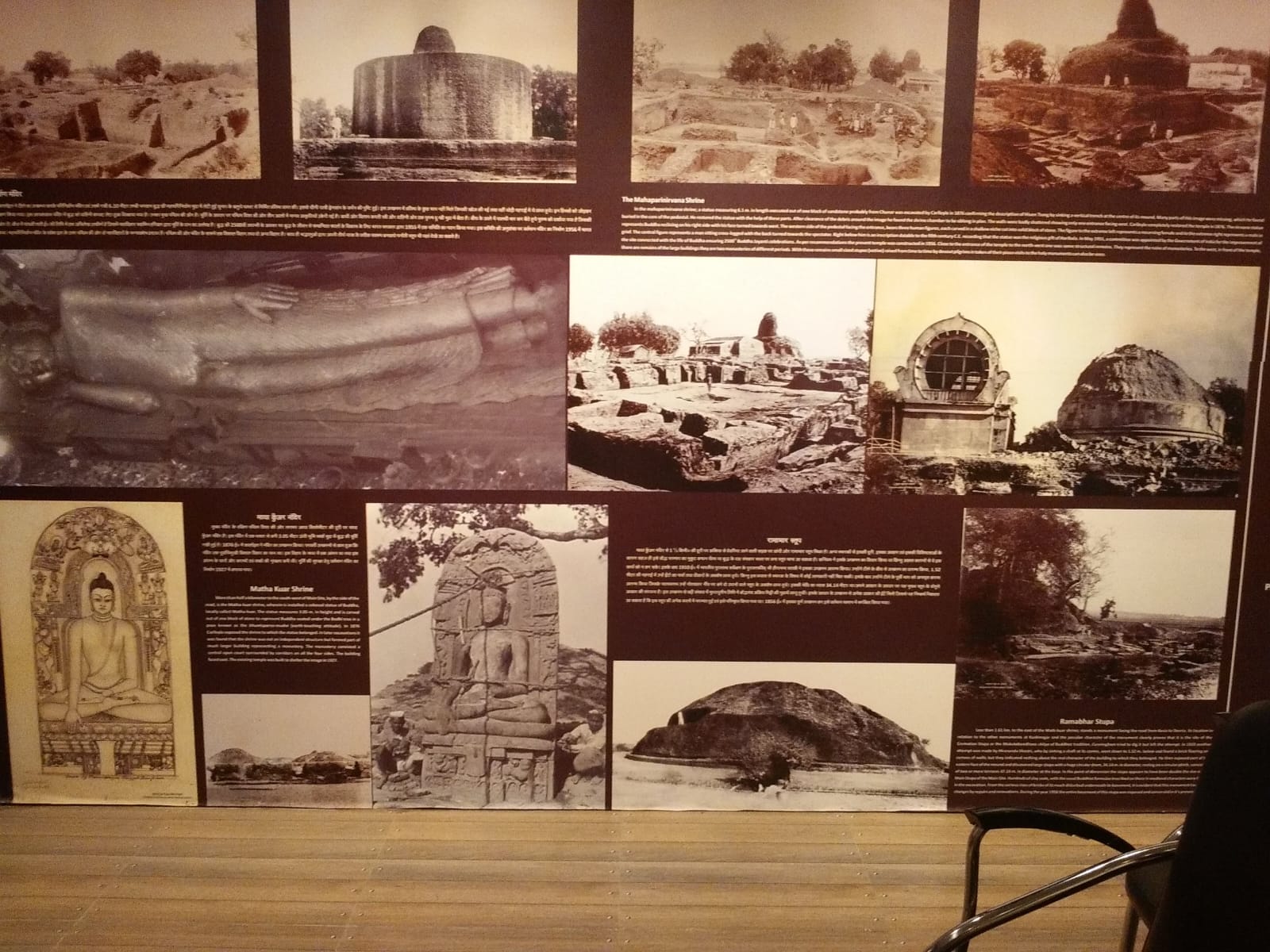

Fieldwork at Kusinagar

Arrival and Initial Work

Between 1877 and 1880, Carlyle traveled extensively in northern India. After leaving Chaora and Bhopa, he reached Gorakhpur, where he remained from June to November. In November, he traveled to Kasya and pitched his camp near the black stone statue of Buddha Bhikshu, among the ruins of Kusinagar.

Although General Cunningham had previously documented the statue (1861–62), he had not conducted thorough excavations. Carlyle immediately began systematic investigations of mounds, ruins, and brick structures, uncovering temples, stupas, and monastic buildings.

Excavation of Temples and Mounds

Near the black stone statue, Carlyle discovered a low, round-topped mound of brick ruins. Excavation revealed the base of a small temple, approximately 23 feet square externally and 10–12 feet square internally. The doorway faced east, and inside the western wall, he found the brick pedestal on which the black statue had once stood.

Outside the walls, he discovered a large black stone slab with an inscription in Kutila script, probably of the eleventh century, starting with “Om namo Buddhdya namo Buddhdya Bhikshune.” Though parts of the inscription were missing, it provided evidence of the temple’s religious use.

Discovery of the Colossal Parinirwana Buddha Statue

Carlyle’s most remarkable achievement was uncovering a colossal recumbent statue of the Buddha, lying on a broken Singhasan in a chamber measuring approximately 30 feet in length and 12 feet in breadth. The statue measured about 20 feet in length and was broken in several places due to ancient damage:

- Upper part of the left leg, portions of the waist, and left arm

- Portions of the head and face

- Parts previously repaired with plaster

To restore the statue, Carlyle excavated beneath the pedestal and Singhasan, recovering many fragments ranging in size from a few inches to several feet. He personally reassembled the statue by hand, restored missing parts with stucco and Portland cement, and painted it with lifelike colors: yellowish flesh tones for the face, hands, and feet; white for drapery; and black for hair.

Restoration of the Temple and Roof Construction

After completing the Buddha statue, Carlyle repaired the surrounding temple. To protect both the restored statue and the temple, he constructed a vaulted roof using:

- Bamboo and mat frameworks

- Cow-dung mixed with clay as a mold

- Keystone bricks for the arch

He emphasized that the roof could only be built after the statue was fully restored, ensuring its protection. This reflected both his meticulous planning and practical ingenuity in heritage preservation.

Other Excavation Discoveries at Kusinagar

During the Kusinagar excavations, Carlyle uncovered numerous archaeological treasures:

- Four-armed Ganesa figure in dark greenish-blue stone, 1 foot 8 inches tall

- Small seated figure of Maya Devi embedded in the front ante-chamber wall

- Broken figure of Viṣṇu from the south side of the great mound

- Fragments of an ornamental canopy of a small statue, probably of Sariputra

- Copper plates and terracotta seals with Buddhist inscriptions

- Small stupas of varying sizes surrounding the main stupa

- Iron hinges and charred wood from temple doors, indicating destruction by fire

- Ancient well, repaired and restored for water use

- Evidence of monastery remains, paved channels, and water drains

These discoveries highlighted both the grandeur of Kusinagar in its prime and the violent historical events that caused destruction to Buddhist heritage.

Search for Pava and Other Buddhist Sites

Beyond Kusinagar, Carlyle undertook a rigorous search for historically significant cities like Pava. This required:

- Traveling long distances on horseback or foot through difficult terrain

- Enduring extreme heat, monsoon rains, and dense thorny forests

- Excavating overgrown mounds and ruins

Despite these hardships, Carlyle remained methodical and patient, guided by historical texts and inscriptions, contributing significantly to the understanding of the geography of early Buddhism.

Carlyle’s Character and Dedication

Carlyle’s writings and actions reveal him as:

- Dedicated and hands-on – personally restoring statues and supervising masons

- Resourceful and innovative – designing roofs and protection systems for fragile monuments

- Scholarly and meticulous – documenting measurements, inscriptions, and fragments with precision

- Resilient and courageous – enduring harsh climates and physically exhausting work

- Selfless and principled – spending his own salary for restoration when government funds ran short

- Passionate about preservation – prioritizing heritage over convenience or personal gain

Even under the most challenging conditions, Carlyle ensured that every site he excavated was properly documented and protected.

Life and Career

- Born in England in 1831, Carlyle initially came to India seeking opportunity, working as a tutor and in museums (Calcutta, Agra).

- He joined the ASI in 1871, appointed by Director General Alexander Cunningham (1814–1893).

- He was First Assistant under Cunningham, conducting surveys across northern India and pioneering studies of prehistoric rock paintings and early coins.

- Prior to Kusinagar, Carlyle discovered Stone Age paintings in Sohagighat (Mirzapur) and excavated sites across eastern Rajasthan, Vindhya Hills, and the plains of Gorakhpur, Saran, and Ghazipur.

- After the ASI disbanded, he returned to Britain in 1885 and lived in straitened circumstances, selling or donating his collections.

- He passed away in 1897, leaving a legacy of meticulous scholarship, practical restoration, and profound respect for Indian heritage.

Legacy and Respect

Carlleyle’s work at Kusinagar exemplifies archaeology with heart. He combined:

- Scholarly knowledge

- Technical skill

- Personal devotion

- Deep reverence for history

He worked tirelessly under difficult conditions to ensure that the Buddha’s monuments were restored, protected, and remembered. For this reason, he is remembered not only as an archaeologist but as a guardian of history, whose work commands lasting respect and admiration.

Conclusion

- C. L. Carlyle stands as a role model for archaeologists, historians, and heritage conservators. His Kusinagar excavation — uncovering and restoring the colossal Nirvana Buddha, temples, stupas, and numerous artifacts — demonstrates what can be achieved through dedication, intelligence, courage, and selflessness. His efforts ensured the protection and survival of Buddhist heritage in India, providing a legacy that deserves enduring respect and admiration.

References

- Carlyle, A. C. L. (1880). Report of Tours in Gorakhpur, Saras, and Ghazipur 1877–78–79–80. Archaeological Survey of India, Vol. XXII. First Assistant, Archaeological Survey of India.

- Archaeological Survey of India. (1877–1880). Excavation notes and site records of Kusinagar and other Buddhist sites.

- Cunningham, A. (1861–62). Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, Volumes on Northern India.

Here I have extracted Mr. Carlyle’s words from his report,

Source:

A. C. L. Carlyle, Report of Tours in Gorakhpur, Saran, and Ghazipur 1877–78–79–80, First Assistant, Archaeological Survey of India, Volume XXII.

“Kusinagara – After leaivng Chaora and Bhopa I went straight to Gorakhpur, where I remained from June to November. In the month of November I started for Kasya, and pitched my camp near the black stone statue of Buddha Bhikshu, among the ruins of Kusinagara.

As this is not the Report of any one season, but only a part of a mere abbreviated summary of the operations carried on by me during the course of two seasons, although I have really very much to say about my discoveries at Kusinagara, yet my notice of them must here necessarily be cut as short as possible.

The black stone image of Buddha Bhikshu, near which I encamped, has already been described in General Cunningham’s Archaeological Reports of the years 1861-62; but as General Cunningham did not make any thorough excavations at Kusinagara, it will now be my business to give a short account of what I myself did in that line there.

Close to the east side of the black statue, there was a low round-topped mound of brick ruins. I immediately set about excavating this mound, and discovered that it contained the base of a small temple, about 23 feet square exteriorly, and about 10 feet square at the floor, or 12 feet above, interiorly. The doorway was on the east side, and against the inside of the western wall I found the brick pedestal on which the great black statue had once stood. On excavating round about the walls outside, I found a large black slab of stone with an inscription, lying near the wall on the south side of the doorway.

This inscription was in the Kutila character, and probably of about the eleventh century. It commenced with the words “Om namo Buddhdya namo Buddhdya Bhikshune”

But I could not find any date, and many of the lines were broken and imperfect; and the ends of most of the lines, and the lower right-hand corner of the inscription, were entirely gone, owing to the shaling off of the stone, which was a kind of black slate.

After having completed this excavation as far as was necessary, I proceeded to the great long mound of ruins called the Matha Kunwar ka kot. Here, towards the eastern end of the mound, there was a high pointed pile of brick, which was the remnant of the core of the dome of a great stupa; and at the base of this pile, a portion of the circular outline of the neck of the stupa could be discerned. Close to the west side of this great mass of ruin, there was a slight, narrow depression; and again, immediately to the west of that, the mound rose again, presenting a flatfish top with an oblong outline. As it appeared to me likely to be the ruins of an oblong-shaped building, and as I was actually in search of the great Buddhist temple containing the famous colossal statue of the Nirvana of Buddha, it struck me that I might possibly have the good fortune here to hit upon some remains of the famous statue.

I then ordered a shaft to be sunk in the centre of this mound. After digging to the depth of about 10 feet, 1 came upon what appeared to be the upper part of the legs of a colossal recumbent statue of stone, but which had apparently been repaired with plaster. I then hurried on the excavations, until 1 had uncovered the entire length of a colossal recumbent statue of Buddha, lying in a chamber which was about 30 feet in length by nearly 12 feet in breadth. The statue was lying on a broken Singhasan. But I found that the statue itself was very much broken, and that many portions of it were wanting. The upper part of the left leg, and both feet, and the left hand, and a portion of the body about the waist, and a portion of the head and face, were entirely gone; and a portion of the left arm, which had been lost at some former period, had been replaced by stucco, or brick covered with a coating of strong plaster. The right arm and hand were placed under the head, and the figure was reclining on its right side, with the face turned towards the west. The stone of which the statue was formed was sandstone, of a mixed colour, mostly dark red and clay colour. The total length of the statue was about 20 feet, and the length of the Singhasan about 24 feet. The thickness of the walls of the temple was nearly 10 feet, and the dimensions of the temple exteriorly were about 47 feet 6 inches by 32 feet. But there was, besides, also an ante-chamber, or entrance chamber, to the west, which was about 35 feet 6 inches in length by about 15 feet in breadth, outside, with walls about 5 feet thick; the dimensions of the interior being 26 feet by 10 feet 6 inches,

I next commenced to repair both the statue and the temple. When about to commence the repairs of the statue, I discovered that some fragments of the statue had been built in under it, into the Singhasan. I then had the greater portion of the statue lifted off from the Singhasan, with great difficulty, and commenced to dig down into the Singhasan for the missing fragments of the statue. In this way, I recovered a great many of the missing portions of the statue, and 1 found that many pieces were buried down under the Singhasan. The fragments which I found ranged in size from a few inches to several feet. I was thus enabled to restore most of the statue with its own fragments, but still several portions were wanting. I had, however, found several rough pieces of stone in the excavations which I made in various parts of the great mound, and I fitted these into the gaps in the statue; and when I fell short ol stone, I restored the remaining portions with a strong compound-like stucco, composed of a cement formed of various ingredients, among which was Portland cement, I having been so fortunate as to obtain a little Portland cement through the kindness of Mr. Peart, who was then District Engineer of Gorakhpur.

I also entirely repaired, restored, and beautified the Singhasan. There were originally four truncated pillars of stone (or stone posts), one at each corner of the Singhisan, but of these, only two were found. The sides of the Singhasan had been formed of slabs of stone, but many of these were wanting, and not more than just enough to complete one side were found. Affixed to the western side of the Singhasan 1 found three small sculptures, displaying three human figures, each carved in a niche cut into a solid block of stone.. The left-hand figure was that of a woman with long hair, and stooping or crouching forwards with her hands resting on the ground. The right-hand figure might be that of either a male or a female; and was in a sitting position, with the head resting on the right, hand, as if in sorrow. The central figure was that of a man, sitting in a squatting position, with his back turned towards the spectator, and his face hidden from view and turned towards the great statue of the Nirvana, On the lower part of the stone of this latter sculpture, 1 was so fortunate as to find an inscription, in two lines, in characters of probably about the second century of the Christian era.

I read this inscription as follows ?

1. Deya dharmoyam Maha Vihare Swamino Haribalasya.

2. Prathimam cheyam ghatitadine Sangha Surena.

This I translate as follows: ‘ ‘The religious gift, to the Great Vihar, of the Lord Haribal. the colossal statue (was presented) to the first united Assembly by Sura”

By the above 1 understand that it was intended to say that the stone with the small sculpture of the sitting figure of a man was the pious gift to the Great Vihar of a nobleman named Haribal, but that the colossal statue of the Nirvana of Buddha had been presented to the first united Assembly by Sura. Now, it is remarkable that a person called Sura was the presenter of a lion-capital pillar to a vihar near the famous stupas of Bhilsa and Sanchi. At least I gather this from the copy of an inscription which General Cunningham was so kind as to send me, and which I read as follows: Sundare Vihare Swamino Sura Sinha-baliputra rupya.

In this inscription some of the words are lost; but I conceive it to mean ‘that Swami Sura presented a lion-whelp sculpture to the Beautiful Vihar.

After having completed the repairs and restoration of the statue, 1 gave it a coating of paint, in order to preserve the stone; and I coloured the face, neck, hands, and feet, a yellowish flesh-colour, and I coloured the drapery white; and I also gave a black tint to the hair. Thus I really made the statue as good and as perfect as ever it was, or perhaps even better than ever it was. I may also further state that 1 myself worked at the restoration of the statue with my own hands, like any common mason. At the same time that 1 was repairing the statue, I also set about repairing the temple. When the ruins of the temple were first excavated, the ruined walls varied in height at various parts from 5 to 6, 7, 8 and in one place nearly 10 feet, measured from outside; but their height inside was much less. But the tops and a portion of the outer sides of the walls being in a broken, shaky, and bulged condition, many parts had to be taken down and rebuilt. I then next commenced to heighten the walls, and I raised them all to the height of 12 feet. The walls had a slope or batter; and the bricks outside, after every three courses, were built in for about 1 1/2 inch with what the native, masons call a khaska~.

The next thing was to roof in the temple. On clearing out the inside of the temple, I discovered a few bricks, in situ, of the remains of the spring of the arch of a vault.

The bricks were set on end, and from the line of curve which their sloping edges indicated, it was evident that the arch of the vault had been a pointed one, meeting at the height of about 13 feet from the floor. I consequently determined to build a pointed arched vault of 12 feet in height. At one end of the building, I also found a few bricks remaining in situ of an arched window; and there had evidently been another window of the same kind at the other end. In the doorway, I also found a few bricks of the spring of an arch, in situ standing on end. In the outer or front entrance chamber, there had also evidently been a small window at each end. I had thus a great vault and five arches to rebuild. But in the inner doorway of the temple itself, I made an interesting discovery. In two hollows, one on each side, at the lower part of the doorway, I found the ancient cup-shaped iron pivot hinges, of the former doors; and with the hinges, I found some fragments of black charred wood, which showed that the doors had been destroyed by fire; and as numerous human bones and various charred substances were found in the outer chamber, as well as in both doorways, it was evident that Buddhism had here been anihilated by fire and sword !

1 must now describe how I built the great vaulted roof over the temple. It must be borne in mind that I had already entirely repaired and restored the great statue, before I commenced to build the roof; and therefore an arch or vault of masonry had to be thrown over the temple, without in any way injuring the precious statue below ! How this was to be done was a puzzle to the native masons ; and one head mason and his men actually ran away out of sheer fright at the difficulty of the undertaking! But I at once saw how it was to be done; and l would have undertaken to build an arched vault, over a shop full of glass and crockery, without removing or injuring a single fragile article.

It only required a little gumption ! I had already built up the two end gable walls, to their required curved shape and height, to serve as a guide for the curve and height of the arch. I then next covered the statue entirely with a large pall or cloth, and over that with soft mats. Over all, I placed a cage formed of mats and bamboos. Then along each side of the interior of the long walls of the chamber, I built up two rough temporary inner walls of brick and clay, 6 feet in height, and about a foot in thickness. On these, from side to side, I placed a close flooring of bamboos and mats, at the height of about a foot above the highest projecting point of the statue and 6 feet above the floor. I then placed a close series of strong bamboo ribs on end, on the two rough temporary side walls and made the top ends of the bamboos from each side meet above, at nearly the height of the required arch, and bound their points firmly together, and united them to a strong ridge pole which I had placed on the tops of the two gable end walls, so that it lay lengthwise, from end to end, along the centre. I then covered this frame-work with a coating of cow-dung, mixed with soft adhesive clay; and 1 thus formed a perfect curved mould for the pointed-arched vault. Then 1 set the masons to build the arch of the vault; and when the arch was sufficiently far advanced, I clinched it with ancient bricks of an enormous size, as keystones. When the vault was completed, the next thing was to take out the frame-work of bamboos, & C. ; and the removal of the whole mass of frame work was effected, piece by piece, by passing the materials out through the two arched windows which 1 had already previously constructed in the two.end walls. After the framework was removed, I next removed the bricks and clay of the two temporary supporting side walls, the materials being carried, bit by bit, out of the doorway. At length, when all was clear, I uncovered the statue and found that it was perfectly intact. Not a single bit of anything had fallen on it, and it had not received the slightest injury of any kind.

As I had found some round moulded bricks in the excavations, which had evidently formed parts of pinnacles, I used them for the same purpose; and I surmounted the roof of the temple with a row of pinnacles. After this, 1 fixed a strong iron barred swivel door, in the doorway of the temple, and I placed an iron railing around the statue; and I also fixed iron bars in the windows.

I also roofed in the outer front anti-chamber, with a sloping roof of sal timber and tiles, and I put a wooden door in the outer doorway of the front chamber.

In the preceding description of my operations, it will be seen that I have stated that I completed the repairs and restoration of the statue before I built the roof over the temple; or, in other words, I built the roof over the temple after I had repaired and restored the statue.

Now it is possible that if this summary report of my operations should happen ever to be read by any engineers, some over-wise engineer may possibly exclaim, “Well, 1 never heard of such a thing! What, first restore or reconstruct a grand statue, and afterwards build a roof of masonry over it?

Why did not the fellow have the common sense first to build the roof, and afterwards to repair the statue?” Well, then, my answer to this would be an effectual one. Hooly and fairly, man! hooly and fairly! Just wait a wee, and I’ll tell you all about it. You see the building which I roofed in was not a dwelling-house, either for you or for me; but it was simply a covering for the protection of a grand ancient statue, of historical interest; and therefore until there was a statue to cover and- protect, or rather until the statue was in such a condition of perfectness as to make it worth while to protect and cover over with a roof, there was no use in roofing in the old temple at all! Now I have already previously stated that, when I first found the statue, it was broken to pieces, and numerous portions of it were lost and wanting. And therefore, when I first set to work to repair the statue, 1 was in great doubt as to whether it would be possible to repair it at all; and at that time I had no hopes whatever of being able to restore it to its pristine condition, seeing that the statue was in a firightfully smashed-up condition, and numerous parts of it were entirely wanting, and could not at first be found anywhere, until I made an excavation underneath the pedastal of the statue, made an excavation underneath the pedastal of the statue, after having had all that then remained of it lifted off to one side. Consequently, until I had made quite sure of being able to repair and restore the statue, I was not going to be such a zany as to build a roof over nothing! Now, the only way in which I could prove or ascertain whether , the statue could be restored or not, washy fitting and joining together all the fragments of the statue which I could find; and after the statue was all joined and put together, it then of course became absolutely necessary to build a proper roof over it, in order to preserve and protect it! Q. E. D.

But now, again, by those whose policy is retrenchment, it may perhaps be asked – And did the Government pay for all this restoration of a musty old Buddhist concern, merely for the sake of a little archaeological recreation? I answer, No! The Government funds which I had in hand did NOT prove sufficient for the completion of the whole work of restoration, in the manner in which I felt that it required to be completed; and so, when the Government funds in my hands ran short, I did not like to ask for any more; and I myself supplied the deficiency (or rather the further funds which I wanted) out of my own salary. On counting the cost, afterwards, I found that in the course of about three months, or from June to September, I had spent over R 1,200 out of my own salary, on the completion of the works at the Matha Kunwar ka Kot. But in this sum must also be included the cost of some extra excavations which I paid for myself. I need hardly say that this expenditure brought me into considerable pecuniary difficulty. Yet I felt that it was necessary.

And finally to all I would say:- Let those who cavil come and see the completed work with their own eyes, and then I shall be satisfied!

Besides the excavation and restoration of the temple and statue of the Nirvana, other still more extensive excavations were carried on in various parts of the great mound of the Matha Kunwar ka kot. The greatest excavation of all was made in clearing and laying bare to its foundations the great stupa close to the back or east side of the temple. When first I arrived at the Matha Kunwar, the whole mound was covered with a dense thorny jangal; and towards the east end, a compact mass of debris of broken brick and earth rose to the height of about 40 feet above the plain. Nothing in the shape of ruins was visible anywhere, except a high pointed, rugged, perpendicular pile of brick, on the top of all which I afterwards found was the remnant of a portion of the central core of the former dome of a stupa. At the foot of this pile, on the northern and southern sides, some slight excavations had been made by some former civil officers, which exposed, on two sides, a small portion of the circular outline of the neck of the stupa. But everywhere else, a solid mound of debris reached completely up to the foot of the ragged pinnacle of brick on the top. The depth of the excavation which I made on the east side, in order to reach the original foundations of the base, or lower plinth, of the stupa, was about 30 feet, and reached to below the level of the fields. I found that what had remained of the stupa, buried below the upper ragged pinnacle of brick, was a circular tower, now about 12 but originally about 14 feet in height, and about 180 feet in circumference. I next, found that this circular tower stood upon a square plinth, the east side of which measured about 85 feet in length; and the height of this plinth, on the south side, was about 4 feet 2 inches. This plinth stands upon another lower plinth, or basement, the east side of which measured 92 feet in length, with a height of about 4 feet 6 inches to 5 feet from the former level of the ground, which is below the present level of the fields. This gives a total height of about 21 feet, to what still remains of the stupa, in a pretty perfect condition. (These are the measurements of the height of the plinth on the southern side; but on the northern side, I found the upper plinth to be about 5 feet 6 inches in height, and the lower plinth about 4 feet in height.) Above and on the top of this height of about 21 feet, there was a sloping pile of ruins, which might be from 8 to 12 feet in perpendicular height, varying according to the point at which it was measured. Above this, there rose a high, rugged, pointed, perpendicular pile of brick, which was about 23 feet in height. This would give a grand total of about 54 or 55 feet in height. General Cunningham calculated the total height of the top of this ruin, from the plain, to be about 58 feet; but, as has been seen, I could not make out more than about 55 feet of height.

I had however to clear off, or diminish, some part of the top of the upper pile of ruin, in order to lessen the top weight, as it overhung, or leaned, slightly towards the temple, and I was afraid of its falling on it.

The circular tower or neck of the stupa stands at the distance of only 13 feet to the east of the back wall of the temple.

The plinth of the stupa is carried on, westwards, to the north and south of the temple;

and the temple in reality stands upon the same plinth as the circular tower of the stupa. The original total length of the grand plinth, from east to west, was thus probably about 150 feet; the breadth of the plinth, at its base, from north to south, being about 92 feet.

But the temple , which I repaired was not the original temple; for the present temple was closely surrounded, on three sides, by the ruined remains of an ancient wall, which extended to within 6 feet of the back of the present temple, while it extended about 10 feet beyond the front of the present temple. The exterior outline of this low-ruined wall of the ancient temple presented a series of horizontal step-like ins and outs, the four corners being thus frittered off by a series of angular recessions. The dimensions of the ancient temple would appear to have been about 85 feet from north to south, by about 52 feet from east to west. There were ancient steps running down from the west side of the base of the ancient temple. These ancient steps were lower than, and about 10 feet distant to, the west of the steps of the present temple; and the ancient step probably originally reached down to the same level as the base of the lower plinth of the stupa.

Close adjoining to the east side of the base of the lower plinth of the stupa, I excavated, a row of small stupas, five in number, and which were of various diameters, namely, 8 feet 4 inches, 7 feet 8 inches, 9 feet, 6 feet, and 3 feet 10 inches. I also found another small stupa, 6 feet in diameter, and in a very perfect condition, adjoining the south side of the basement of the great stupa. But in the course of my general excavations, I found a numerous assemblage of small brick stupas, scattered over the eastern half of the great mound.

At the north-east corner of the lower plinth or basement of the great stupa, down at the very foundation of the building, and at the lowest point or greatest depth reached in the excavations, I found a red terra-cotta figure of Buddha, standing with his right hand raised in the attitude of teaching. The figure had lost the head, but I afterwards found the head among the earth a short distance off. When the head was fixed on, I found that the whole height of the figure was 2 feet 2 inches. In the excavation to the east of the stupa 1 found a metal bell, with a portion of a thin iron rod attached to it; and I also found a fragment of another bell, and three more iron rods to which bells had been attached! The inference which I drew from this was that a row of bells had been attached to the rim of the stone umbrella which surmounted the stupa. I also found, in the same place, a four-armed figure of Ganesh, in dark greenish-blue stone, which measured 1 foot 8 inches in height. I should also mention that I found a small sitting figure of Maya Devi, in dark greenish stone, embedded in the inside of the wall of the front ante-chamber of the temple. 1 also found a broken figure of Vishnu in the ruins of a building which I excavated on the south side of the great mound. I had all these sculptures carefully fixed inside the temple.

But the most interesting of the small sculptures which I found in the course of excavation, were two fragments of the ornamental side stone, or encircling stone, or. canopy, of a small statue, which, from a portion of an inscription still remaining on the back of one of the fragments, would appear to have been a statue of Sariputra, who was one of the most famous and respected of the disciples or followers of Buddha. The fragment contained only the right half of the inscription, which 1 propose to read as follows:—

……..(te) Sanyuvacha tesam cha yo nirodha………….Sanggha Sariputrasya.

The two fragments of sculpture referred to above, evidently formed the top and a portion of the left side of the ornamental encircling stone, or canopy, of a small statue. The top piece displays a small sculpture of the Nirvana of Buddha, 2 1/2 inches in length. It shows Buddha lying on his right side, on a couch, exactly as in the great statue in the temple. On the other fragment, there were two sculptures; one showing Buddha sitting cross-legged, and the other, below it, showing Buddha standing in the attitude of teaching; but the upper sitting figure had been broken off at the waist.

In the same excavation I also found a small plate of copper, about 41/2 inches in length, by about an inch in width, with the Buddhist profession of belief inscribed on it, in three lines, in characters of probably about the fifth century of the Christian era. 1 read the inscription as follows—

Ye dharmma hetu prabhava hetu tesham Tathagatahya vadata teshancha yo nirodha evam vadi Maha Sramanah.

At the back of the temple I also found upwards of twenty terra-cotta or burnt clay seals, with the Buddhist profession of faith impressed upon them, in characters of a later period. The largest of these seals had also three stupas represented on it, in bold relief.

I also made a partial excavation on the central highest part of the mound, to the west of the temple, and I uncovered a portion of the walls of some chambers, which appeared to have belonged to a monastery. And I also uncovered a portion of a pavement, and a drain or water channel, running through between the buildings.

I also discovered an ancient well, at the depth of about 10 or 12 feet below the surface of the mound, at the distance of about 60 feet, to the west of the temple. 1 cleared out this well, and repaired it, and built up the sides of it to a level with the top surface of the mound. This ancient well was originally square below, terminating in a slightly circular shape at the top. There is now good water in the well, and people draw water from it.

According to Huen Thsang’s account, there was also a lofty stone pillar standing near or close to either the temple, or vihara, or the great stupa, of the Nirvana; and on this pillar there was an inscription which recounted the circumstances of the Nirvana of Tathagatha (Buddha). But as Huen Thsang says that—mais on n’y a pas ecrit le jour ni le mois de cet evenement (but they have not written there either the day or the month of this event), the inscription could not have been of any historical value in settling the true date of the death of Buddha, I searched everywhere for this pillar in the course of my excavations, but I could not find any trace of it. But as my excavation to the south side of the great stupa was somewhat less extensive than on the other sides, it is just barely possible that the pillar may still be lying buried under the earth and debris, at some short distance off to the south of the great stupa; but in that case the pillar must have been situated at a greater distance from the stupa than would appear from the description of Huen Thsang. For immediately after his description of the stupa Huen Thsang says that—On a eleve en face une colonne en pierre, &c. (They have raised a pillar of stone in the face thereof,) It is difficult to say what side Huen Thsang meant by the face; but I can certify that no pillar could be found anywhere adjoining the stupa. – – A. C. L. Carlyle